PROGRAM NOTES: Modest Mussorgsky’s PICTURES AT AN EXHIBITION

Posted on April 9, 2018

PYP will perform Pictures at an Exhibition on Sunday, May 6, 2018 in the Arlene Schnitzer Concert Hall. Program notes written by Carolyn Talarr, PYP’s Community Programs Coordinator.

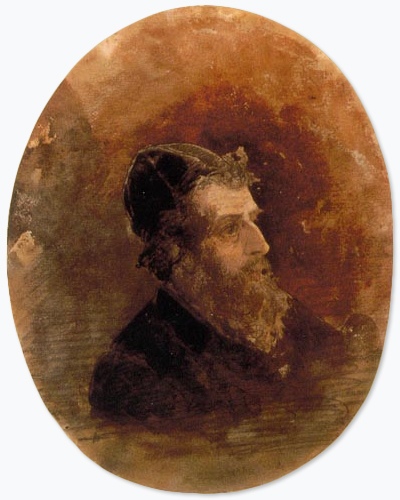

Modest Mussorgsky: a son of a serf-owning ancient noble family who paradoxically championed a populist nationalism even after losing the family fortune when the serfs were freed; a man who began as a soldier in an elite regiment and ended a penniless, homeless alcoholic; a composer with virtually no formal composition education who created some of the most cherished, poetic, evocative music ever to come out of Russia.

At the start of Mussorgsky’s composing career, even his friends called him “half-idiot”, “flabby and colorless”, until the opera Boris Godunov changed their minds. Tchaikovsky, whose Fourth Symphony PYP performed earlier this season, also weighed in on him. Tchaikovsky graduated from and taught at conservatories, and was thus far more ‘westernized’ in his perspective than were “The Five”, also called “The Mighty Handful”, of Russian nationalist composers. Tchaikovsky wrote to Nadezhda Von Meck, who PYP audiences may recall was the patroness with whom he began an epistolary relationship while composing the Fourth Symphony:

Initially unappreciated, yet undeniably beautiful and original in its own rough way, Pictures at an Exhibition can be seen as a synecdoche for Mussorgsky’s brief life and career.

Image source: Wikipedia

From here on, so much excellent, quotable writing has been generated about Modest Mussorgsky and Pictures that the fairest thing to do is to curate an “exhibition” of some of the best work (purely subjectively determined of course) and let it speak for itself. Some of the facts cited in various articles may differ with each other (e.g. Which specific artworks are the vignettes referring to and how many were in the exhibition originally? How exactly did Hartmann die? etc.) but every article affords a richer, deeper awareness of the forces behind this uniquely powerful, unabashedly programmatic and synesthetic ‘work of arts’.

Mussorgsky the man:

The New World Encyclopedia site (adapted from and improved on the Wikipedia entry on Mussorgsky) offers the most apt brief biographical overview. Pictures is mentioned only tangentially; the article covers the entire arc of Mussorgsky’s life and work.

This fascinating contemplation on Hartmann, Mussorgsky, and Pictures places the composer and the composition in their specific Russian sociohistorical context. The emphasis is much more on art and politics of the work than on musical analysis.

The music:

There are many books on Mussorgsky, even on just Pictures, but for anyone who is interested in getting an informed overview of the various interpretations, the musical structure, and overall significance of the work, in my opinion the most easily readable, comprehensive take is a 2009 dissertation by Svetlana Nagachevskaya. Pictures at an Exhibition: A reconciliation of divergent perceptions about Mussorgsky’s renowned cycle adduces biographical, socio-historical and musical analysis, including some sources hitherto available only in Russian, to support the author’s own integrated reading. The dissertation can be downloaded here (click the ‘download’ tab on the right) and is easily skimmable for parts of interest.

Nagachevskaya’s summary perfectly captures many of the artistically revolutionary, Russian-yet-universal aspects of this piece that modern audiences perhaps take for granted, but that together help create the work’s broad emotional, human appeal:

For this context we’ll leave the “atonality, polyharmony, and polytonality” just at naming them, but suffice to say that Mussorgsky’s lack of conservatory training actually stood him in good stead as he tried to find adequate means to make his music communicate real, ‘natural’ life. Rules for rules’ sake were anathema to him, for they separated the work of art from the immediate world. Similarly, the innovations are not innovations for innovation’s sake, or based on some cerebral theorizing. He wrote, “Life, wherever it reveals itself; truth, no matter how bitter; bold, sincere speech with people—these are my leaven, these are what I want, this is where I am afraid of missing the mark.”

The unheard-of, nearly chaotic variety of sounds is partly what made Mussorgsky’s more traditionally-inclined contemporaries’ skin crawl, but in the context of the ‘pictures’, and what he was trying to communicate, it makes perfect sense. Eventually, once people understood Mussorgsky’s work for itself instead of dismissing it as merely idiosyncratic and in need of tidying up, such influential 20th-century masters as Stravinsky and Shostakovich freely acknowledged Mussorgsky’s instinctive musical and programmatic explorations as having been deeply influential on their work.

Next, as a representative of the many orchestrations that have been made of Pictures, which was originally composed for piano: not a reading, but a video, this exploration by Allegro Films of Russian pianist Vladimir Ashkenazy’s conducting of Slovenian violinist Leo Funtek’s orchestration of Pictures is an eloquent, complex tribute to Mussorgsky’s peculiarly Russian, peculiarly melancholy character and artistic style. Ashkenazy discusses Ravel’s “magnificent”, yet regrettably French, orchestration at length; he compares Ravel’s version unfavorably to Funtek’s, which he feels better captures the original piano version’s sincere, Russian roughness and ‘dark soil’ muddiness. (A recording of Ashkenazy’s own orchestration, which came later, is here.) The interview, and the performance in parts 2 and 3 of the 3-part film, are eminently worth watching.

To look more deeply into the vignettes themselves, we return to reading: I will quote Marianne Tobias’s program notes from an Indianapolis Symphony performance in 2016 as a basic framework. Tobias’s notes are in indented quotes below; at some points I have added some interesting details that were chosen on a completely subjective basis, bracketed and in blue; many of those details are quotes from Nagachevskaya.

The surviving original works by Hartmann will precede the vignette they inspired, but it’s important to note, though, that pictures for only five of the episodes still survive, and the identity of others is still contested. Further, most commentators agree that Mussorgsky’s musical homages to his beloved dead friend imbue Hartmann’s original drawings with a spiritual and artistic scope that they don’t necessarily convey on their own. As pianist, orchestrator, and conductor Vladimir Ashkenazy, for example, says in the video mentioned above: “It’s not so much to do with what Hartmann saw in those pictures, but with the creative impulse it gave to Mussorgsky.”

——————————————————————————————-

[Tobias makes this claim probably based upon the fact that in a letter to Stassov, Mussorgsky explicitly wrote that “my physiognomy is visible in the promenades.” There is, as one might predict, controversy over whether this line is to be taken literally or metaphorically. Further analysis of the critical interpretations of each individual promenade is available in Nagachevskaya’s dissertation.]

1) We arrive first at Gnomus (The Gnome) clumsily running with crooked legs” which is represented by a grotesque Nutcracker originally designed by Hartmann as a Christmas present for children. Note the sudden starts and stops as The Gnome flails about in his movements. A savage ending completes this section.

2) We move again via the Promenade, marked “moderato commodo assai e con delicatezza” to the watercolor: Il Vecchio Castello (The Old Castle), wherein we view a troubadour singing (sadly) to his beloved in front of the medieval building. The troubadour, who is unsuccessful in wooing his sweetheart, is represented by the doleful tones of alto saxophone. The music ends quietly with throbbing rhythms.

[Ravel’s unusual alto sax solo is highly controversial; other orchestrations have instead deployed the English horn and other winds.]

3) We re-enter the Promenade, marked “moderato non tanto, pesamente” leading to a picture of the beautiful Tuileries in Paris. A tiny, tri-partite scherzo depicts children playing amid scolding nannies. The music moves lightly, quickly, full of sparkle and delight.

4) Bydlo depicts a huge Polish cart drawn by oxen. The heaviness of the cart and the oxen is presented via solo tuba and slowly moving orchestration thumping in 4/4 meter. The music quiets as the cart moves away at the close.

[The interpretations of this vignette and the Samuel/Schmuyle vignette are the most contested and politically laden. According to some commentators, it’s just a musical illustration of a picture; another thinks it’s an indictment of how the Russians treated Poles in the 1870. Several Russian commentators, understanding Mussorgsky’s politically progressive sympathies, contend that the vignette doesn’t concern Polish oxen at all but is rather a coded illustration of the oppression of Russian serfs; according to Nagachevskaya, “He focused all of his compositional strength on depicting the enormous suffering of the poor, desperate, and oppressed Russian peasants. Bydlo goes far beyond the naturalistic imitation of the wooden cart and the oxen that pulled it.”]

Image source: Wikipedia

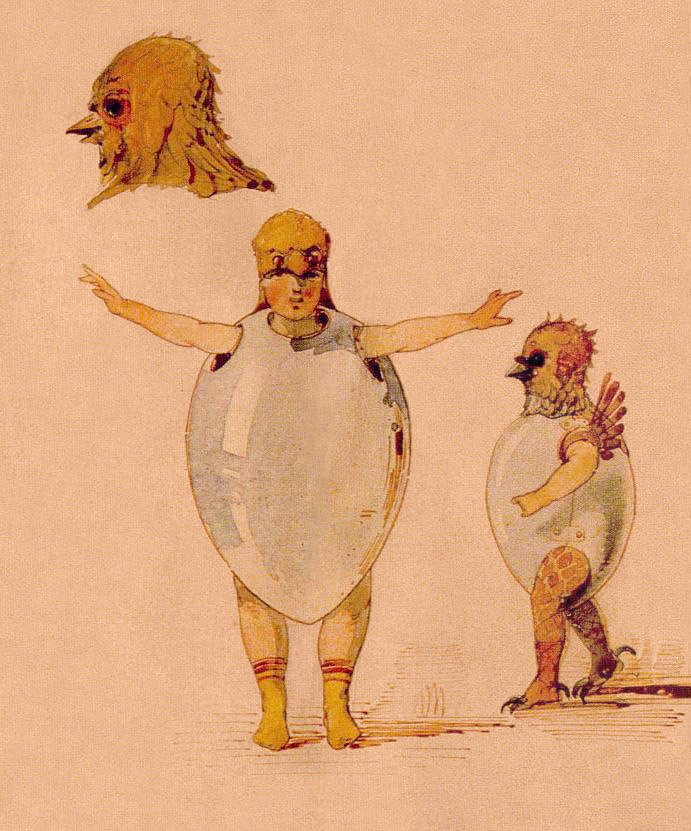

5) …the light- hearted Ballet of the Chicks in their Shells for which Hartmann had designed costumes featuring eggshells with bright yellow canary heads for the ballet The Elf of Argyle or Trillby. Quick chirps unmistakably represent the energetic chicks who bounce happily amid winds and pizzicato strings.

The Ravel version omits the Promenade theme at this point.

Image source: Wikipedia

[From the title on, this is probably the most controversial vignette of the entire piece. Nagachevskaya summarizes the two sides:

“…according to Andrei Rimsky-Korsakov, Samuel Goldenberg und Schmuyle was Mussorgsky’s original title. There are two different perceptions about the psychological meaning and content of this piece. Western and Russian scholars could be {roughly} divided in two groups: one group claims that this piece is a{n anti-semitic} caricature or a grotesquerie. {Mussorgsky’s well-known antisemitism, which stood out even in an era of general antisemitism, supports this claim.} The other, rather merciful, group states that this piece is about a personal tragedy that reveals a deep social drama. The internal evidence of the piece leads me to believe that poor old Schmuyle should be taken seriously because he, being placed in unfortunate circumstances aggravated by the rich man’s mistreatment, sorrowfully appeals for compassion rather than laughter.”]

[This vignette, among others, demonstrates a central tenet in Mussorgsky’s idiosyncratically populist, programmatic musical philosophy that is best captured in Mussorgsky’s own words. “Art is a means of communicating with people, and not an aim in itself. This guiding principle has defined the whole of his [i.e., “my”, as Mussorgsky was referring to himself here] creative activity. Proceeding from the conviction that human speech is strictly controlled by musical laws (Virchow, Gervinus), he considers the function of art to be the reproduction in musical sounds not merely of feelings, but first and foremost of human speech.” {Emphasis mine. Quote from the New World Encyclopedia entry mentioned above, although I’m sure it can be found other places as well since it was an autobiographical sketch Mussorgsky wrote of himself.}]

Image source: Wikipedia

8) Sepulchrum Romanum; Con mortuis in lingua mortua (Catacombs; With the dead in a dead language), per Stasov, notes, “Hartmann represented himself examining the Paris catacombs by the light of a lantern. There are two sections: Largo and Andante. Mussorgsky wrote in the score, “The creative spirit of the dead Hartmann leads me towards the skulls, invokes them; the skulls glow softly from within.”

The Promenade theme re-emerges within the context of the Andante.

Image source: Wikipedia

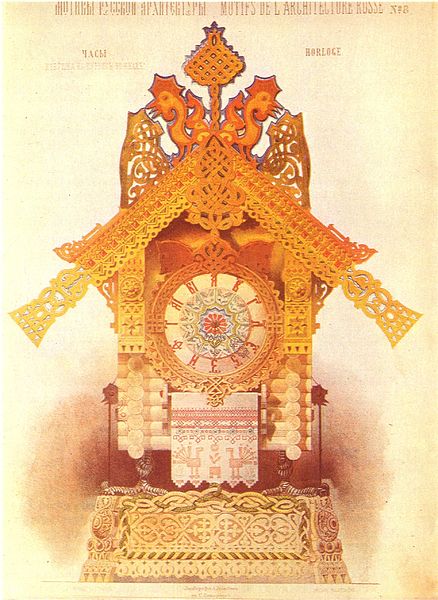

Evidently Viktor Hartmann memorably dressed as Baba Yaga for a costume ball back in the 1860s; this fact could explain the amount of imaginative energy expended on a children’s story, in that it was a tribute to the spirit of his imaginative friend.]

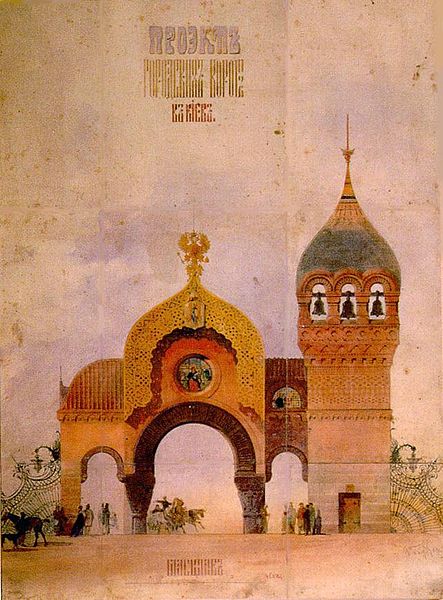

10) A coda leads to the final movement, The Great Gates of Kiev .

Image source: Wikipedia

The final movement is marked maestoso con grandezza, based on the sketch which was Hartmann’s design for the city gates at Kiev, conceived “in the ancient Russian massive style with a cupola shaped like a Slavonic helmet.” It was inspired as a tribute to old Russia, a piece of heartfelt nationalism. The music opens with an expansion of the opening promenade, includes a baptismal hymn from the Russian Orthodox faith, and moves steadily to an enormous climax and glorious tribute colored by tubular bells to Tsar Alexander II who had survived a nearly successful assassination.

Nagachevskaya offers a perspective on the Great Gate of Kiev from the then-young brilliant Soviet/German composer Alfred Schnittke, which has not otherwise been translated into English as far as I can find:

—————————————————————————————-

With any luck, this ‘exhibition’ of a mere sampling of the immense amount of thinking surrounding every note of Pictures at an Exhibition has shown that there is so much more to the work than meets the ear. Because of the openhearted, ‘undoctored’ humanity of his compositional style, however, what audiences do hear, even knowing none of the history or musical innovations, is so completely entertaining and moving in itself as to have made Pictures a keystone of the concert repertoire. Through Pictures as well as his other opera, orchestral, piano, and vocal works, Mussorgsky pushed the boundaries of contemporary music in a way that was completely true to his complex worldview, paid the price for being too far ahead of his time, and died without knowing that not only his fellow Russians, but the world, would come to love his works exactly as he wrote them.

5 Comments :